London’s Lost Venues at the V&A is shaping up to be one of the most important music culture exhibitions in years. Set to open in 2026, the show invites the public to help document the city’s disappearing DIY and grassroots music infrastructure—from sweat-soaked basements to flyered-up toilets, pirate radio towers to torn leather booths. If it had a soundsystem, sticky floors, or a bouncer who once turned you away, it might just belong in a museum now.

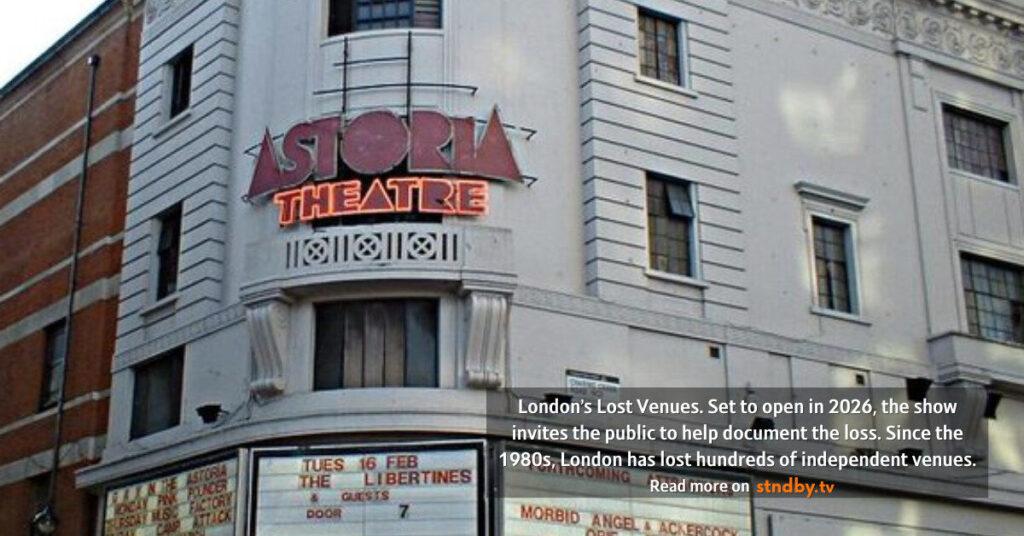

You can’t help but feel the shift. Since the 1980s, London has lost hundreds of independent venues. Some fell to gentrification, others to apathy. What used to be all-nighters in Shoreditch warehouses or punk gigs in squatted pubs now live on in grainy flyers and hazy memories. This exhibition aims to bring that ephemera to life—and it’s asking for your help to do it.

An Archive Built from Memory

The V&A is calling for public submissions to help shape the show, with a focus on music spaces that operated between 1988 and 2025. It’s not about preserving the past for nostalgia’s sake. It’s about recognising these spaces as vital cultural archives. If you’ve got an old ticket stub from Bagley’s, a blurry photo from the Astoria, a rare dubplate, or even a toilet door covered in graffiti from Rhythm Factory—now’s your time.

Submissions are open until Saturday, 31 May 2025, and the V&A is accepting everything from flyers and posters to set lists, instruments, clothing, and equipment. This is DIY history, pieced together from the fragments left behind after the party ends. You can contribute by contacting the museum directly at [email protected]. There’s no dedicated webpage for the exhibition yet, but general updates will appear on the V&A’s official site.

From Camden Palaces to Croydon Basements

Expect the exhibition to cast a wide net. This isn’t just about Soho’s storied past or the usual suspects. It’s as much about a south London rave held under a railway arch as it is about the final nights of The End or Plastic People. The V&A is interested in those hyperlocal ecosystems that fed subcultures: jungle nights with hand-drawn posters, dub sessions in church halls, squat gigs powered by stolen electricity. The places where things got loud, messy, and beautifully out of control.

Each artefact tells a story of a night that changed someone’s life. A drum & bass tape sold outside Blackmarket Records. A flyer for a grime set that never made it to YouTube. A photograph of a half-collapsed roof where a warehouse rave went too hard. These venues may be gone, but their vibrations still echo—and this show wants to bottle that.

A Museum Exhibition with Teeth

The V&A, known more for its fashion and design collections, is leaning into its commitment to music culture with this one. Past exhibitions like “David Bowie Is” and “Club to Catwalk” hinted at the institution’s ability to present subculture with respect and depth. But this project feels more grassroots in intent. It’s messy, decentralised, crowdsourced—and that’s the point.

There’s something powerful about the idea that the things we left behind—beer-soaked posters, cracked 12”s, scrawled set times—might now sit behind museum glass. But the hope is that this exhibition doesn’t sanitise the past. It should smell like a soundsystem and feel like the bassline’s about to drop. If it succeeds, it won’t just be documenting history—it’ll be reigniting it.

Why This Matters Now

London’s independent music venues have been under siege for decades. Licensing laws, property development, pandemic closures—it’s been a brutal combination. In the wake of COVID-19 and ongoing battles over rent, countless spaces simply didn’t reopen. Meanwhile, the rise of sterile “multi-purpose event spaces” continues to flatten what used to be a dynamic, chaotic scene.

That’s why exhibitions like this matter. They don’t just celebrate the past—they remind us what’s at stake. These were not just venues; they were lifelines for marginalised communities, training grounds for future headliners, refuges for weirdos and ravers alike. They built scenes from scratch, no sponsors, no PR—just vibes and word of mouth.

How to Submit Your Memories

The V&A wants your stories, your flyers, your busted amps. If you’ve been part of London’s music underbelly between 1988 and 2025, this is your moment to mark it. Submissions are open now, and the deadline is Saturday, 31 May 2025. Email [email protected] with details, images, or questions about what you’d like to offer. The curatorial team is actively reviewing submissions and will get in touch if your piece fits the show’s scope.

And while the exhibition doesn’t have its own landing page yet, you can stay looped in via vam.ac.uk—the official website for the Victoria and Albert Museum.

More Than Just Nostalgia

This isn’t just a chance to relive old nights. It’s a chance to reframe the conversation about what matters in cultural memory. London’s Lost Venues at the V&A isn’t about the superstar DJs or the platinum plaques. It’s about the sticky carpets, dodgy electrics, and the people who showed up before the headliner even played a note.

Because maybe the most punk thing we can do now… is remember.

Cultural loss isn’t just about buildings — it’s about memories, communities, scenes that disappear overnight. We’ve already dug into the broader picture in our piece on UK music venues in decline, but this exhibition brings that slow erasure into sharp, physical focus. It’s not theory — it’s ticket stubs, sweat-stained flyers, handwritten setlists.

And while the past is being archived, the present moves too. Just down the road, places like Brixton Academy still carry the torch. LCD Soundsystem’s 2025 Brixton dates prove some rooms still throb with life — but for how long?

Credit for main picture, London Astoria, from the outside taken by C Ford March 2004